By: Konstantin Kiriakov

Introduction

Introduction

When using Saussure’s model of

signs, the concept of a film or movie *1 (the signified) is different from the

film itself (the signifier). Film, as a physical object; with the exceptions of

prequels, sequels, remakes and adaptations, is independent and unique from one

another. It can range from a variety of narrative or visual styles as well as

be distributed in a variety of different ways. The film signifier can encompass

the impressionistic study of light filmed on 32 mm film, to a Fantasy picture

shot on a Red One camera; and be projected on a wall or streamed over the

internet. A film can be self reflective or hide its inner workings, making them

an invisible art. In other words, film as a physical object can be many things,

and is not easily, if not impossible to describe, however, our idea of a film,

is for the most part ossified and agreed upon. Film’s signified, elicits the

idea of a visual representation of a story or series of events, which are

psychologically motivated, that culminate and inevitably lead to an ultimate

solution or catharsis. The mere fact that we have a working definition of film

demonstrates this preconceived notion. Therefore, we have predisposed Attitudes

or expectations towards film. A film may or may not match these

predisposition's, but whether they do or not is correlated to the way in which

we evaluate what we have seen.

When a film reaffirms these

preconceived notions the audience will experience enjoyment or jouissance, however

if the film operates using unexpected or foreign conventions and codes the

audience will react in one of two ways; they will either negotiate this new

model or reject it.*2 For example, if you

expect to see a comedy film, and instead encounter a dark humoured drama

dealing with heavy material, you may still enjoy the film because it used codes

that you are familiar with or prefer. You may initially experience shock, but

once you renegotiate the film with your overall attitude towards cinema and re-evaluate,

your experience will be positive. Contrarily, If you expected to see a Romance

film about a man and woman reuniting in a luxurious hotel after a year, and you

see Last Year at Marienbad (1961); without any knowledge of Alain

Resnais or the French New Wave, Surrealism, or Avant-Garde cinema; you would

reject it because it uses codes which are contrary or unfamiliar to the ones

you are programmed with, making the decoding process impossible. Put simply, we

all have predisposed attitudes and expectations towards film, which have some

effect on the way we evaluate films. These predisposition's includes the

Definition of Film, Trends, Hype, and Judgment, all of which have a direct

influence on our reasoned action towards the films we see.

Theory

TRA (The Theory of Reasoned Action)

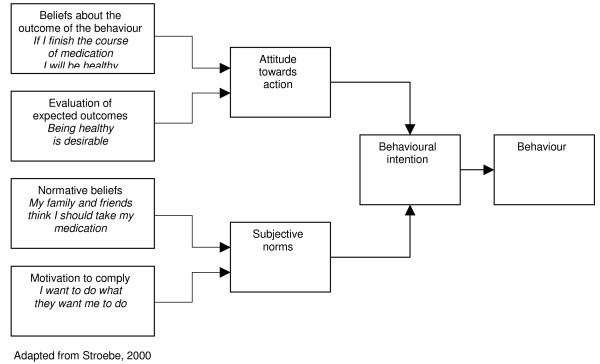

In order to understand the

attitudes and expectations we have towards cinema we must first understand the

two major factors which develop these attitudes. According to the Theory of

Reasoned Action developed by Martin Fishbein and Icek Ajzen, we can see that a

person’s behaviour is based on the sum of their attitude and subjective

norms.

Example:

B = (Attitude)W1 + (Subjective Norms)W2

B:

Behaviour.

Attitude:

The sum of one’s beliefs toward performing a behaviour, as well as its

consequences.

SN:

One's subjective norms, derived from beliefs from others as well as one’s

compulsion to comply, related to performing the behaviour.

W1,2: empirically derived

weight, determining the behaviour's viability based on desirability and

reason.

Put into simple terms, an

individual’s notion of a behaviour is based on beliefs developed by internal as

well as external sources. This attitude has an effect on the way we perceive

and evaluate the behaviour in question. Martin Fishbein stated that initially

an individual responds to new information by developing or reflecting on

beliefs about the object or action. If a belief already exists then it will

most likely be modified. Then, the individual will assign values, according to

importance, to each attribute that the belief is based on, and create an

expectation or modify an existing one. Martin Fishbein and Icek Ajzen even go

as far as to say that this model can be used to predict one’s behavioural

intention (the willingness to perform a behaviour); the same way a friend can

recommend a film to us, by knowing our personal taste (Attitudes and Subjective

Norms).

In

the context of cinema, Martin Fishbein’s and Icek Ajzen’s model should look

something like this:

Expectation = (Definition of Cinema + Judgments)W1 + (Trends + Hype)W2

Attitudes

Definition of film

In every new art form, during its

inception, there is a period in time where it grows and matures into something

that can be mapped and quantified. Boundaries are placed dividing it from other

forms of expression or objects. Cinema has been around for a little over a

century, and has become heavily sutured into our culture as well as daily

lives. It has existed before our conception, as well as the previous

generation’s; making it, at least in our minds, always present. We cannot

picture life without cinema or perceive cinema as a new foreign medium.

Therefore, we have developed and programmed certain ideas or codes of what

cinema is, as well as what it should be. If we were asked to create a facial

composite of film, we would probably say something about its narrative

structures, genres, and length. All of these features contribute to our

attitude towards a film, regardless of whether or not we have seen it, and

create mixed emotions when the face (film) does not match our composite.

Narrative

Structure

It is human nature to attempt to

find structure and meaning in all things, which is the reason why we can

understand editing and montage. However, in order to obtain the preferred

meaning, the one intended to be understood by the institution, the narrative

must use certain codes and conventions which help us infer and decode its

meaning. So, naturally when we go to see a film, we expect to see a visual

dramatization of a fictional or factual narrative, according to a specific

structure which aids us in understanding its meaning. We expect to be given

enough knowledge to understand the context of the events taking place, and that

it is delivered in a clear and concise manner, which is not too overbearing or

obvious. This is achieved through various narrative devices, such as Point of

View Shots, Dialogue, Audience Surrogates, Narration and Inter Titles,

etc.

Every film has a register, that

is to say a model of reality which it follows from beginning to end. The most

common register is that of narrative reality, meaning the consistent and

coherent linear chain of events which inevitably leads to some sort of

conclusion. Using this model, the diegetic world must obey a set of laws or

rules which the film has established, in order to give the illusion of

credibility. These films may have unrealistic elements, such as aliens (E.T.:

The Extra-Terrestrial 1982) or magical candy (Willy Wonka and the

Chocolate Factory 1971), but as long as the characters and physics of the

world follow and adhere to its own perpetuated reality, the film will be

credible in the viewer’s eyes. However, in the case of films such as Man

With a Movie Camera (1929), where narrative reality is purposely removed or

disrupted an audience member may still accept the register (by switching to the

new form of discourse) only if they are aware of its syntagmatic codes and

existence. The average viewer on the other hand, will be unable to suppress

this attitude because they are only versed in a single form of filmic

discourse. For example, a translator can jump between conversations in different

languages, even if the sentence structure and grammar may be different. While a

individual versed in a single language can only understand that form of

discourse, and even have trouble understand certain dialects of it.

We also expect to know as much or

more than the character that the story revolves around. A film typically uses

open or restricted narrative modes to tell the story. The open narrative mode,

provides the viewer with all of the information pertaining the narrative events,

creating tension, like the film Frenzy (1972) where the film reveals the

murderer in the beginning of the film creating tension whenever a character

comes into contact with him. The restricted narrative mode provides a limited

amount of information, often matching that of the protagonist. In any case, by

the end of the film we expect to know all of the information pertaining to the

entire ordeal. Even in the case of a mystery film, such as Sherlock Holmes

(2009). As an audience we understand that we are incapable of matching his

powers of deduction. However, we expect to know just as much as him by the time

the film ends, whether it is through Dr. Watson inquiring how Holmes solved the

case or Holmes proving his intelligence to the villain before he apprehends

them.

(Warning

this clip contains SPOILERS that may potentially ruin the film, A spoiler free example can be seen HERE)

Genres

If the narrative structure is

thought of as the center of the film then the genre can be thought of as it’s

wrapper. The genre is the framework in which the filmic codes and narrative

devices follow. For example, a horror film will drop the sound levels and have

the character slowly approach a dark and ominous object to elicit reactions, such

as tension, shock and fear. (CLIP) The Documentary

film, not being limited to space or continuity, delivers a canon of knowledge

through a transcendental entity or narrator. (CLIP) We understand these

conventions because of our attitude towards these genres. Genres use specific

conventions and narrative registers, which we have grown accustomed to, and

familiar with. These conventions are used to elicit an emotional response,

specific to the genre. This is why we are more or less critical with certain

genres then others; we adjust our weighted values, because we are aware that

the film is highlighting specific conventions all the while ignoring others.

For example, when we watch an action film such as Mission Impossible (1996),

we are not as concerned about realism or even quality of script, than a film

like Kings Speech (2010). Now, we have established that we have

preconceived notions of what we expect to see and how we expect it see it, but

we also expect to see it within a certain time limit.

Time

Span

All visual media has a certain

time limit which we are programmed to accept. We expect to see individual ads

or commercials for 30 seconds or less, internet videos for a few minutes,

Television shows and programming for 30-60 minutes, and Films for around 120

minutes. Ever since the 1960s films have been averaging around 120 minutes (2

hours) of run time, making this the standard time frame. Even though a film

that is over 70 minutes long is considered to be a feature length film,

encountering one may lead to disappointment since it doesn’t meet your

expectation of seeing a 2 hour film. This also applies to films that are over

180 minutes (3 hours), such as Lord of the Rings (2003), Once Upon a

Time in America (1984), which prolong the desired outcome, creating

frustration or impatience.

Judgment

We have established the initial

beliefs that we have developed about cinema, however these beliefs are

constantly refined when we encounter trailers, interviews of cast members,

developer diaries, etc. Our definition and attitude of film stays the same; we

merely appropriate it according to additional information provided by the

teaser, trailer, etc. One’s definition of cinema stays the same, but their

weighted values may shift making things more or less important than before. For

example, when we see the a trailer for Indiana Jones we can assess that the

film will be dynamic and have plenty of action. It will also use Religious

theology which may add a mystical or super natural element to some and offend

others. We are also introduced to the villains (fundamentalists as well as

foreign military), and Indy’s Love interest which suggests that the film will

be somewhat nationalistic as well as a adopt the Medieval Romance model, where

a knight (Indie) goes out and slays the Dragon (foreign military) and save the

damsel in distress. (CLIP)

In other words this is the stage in which we judge a book by its cover.

However, sometimes the trailers are misleading, presenting a narrative or

framework which is very different from the one used in the final film. For

example, the trailer for In Bruges (2008) promises a Guy Richie styled

gangster comedy, with crude wise-cracking criminals that engage in over the top

violence which have little to no consequences in the diegetic world. (CLIP) However what the film delivers is criminals who

suffer terrible consequences due to the atrocious nature of violence. As stated

before the evaluation of a film comes from the culmination of expectation and

experience, where being unfamiliar with the codes and conventions used in a

film would ultimately lead to disappointment or confusion. However, you can

also be disappointed in a film even if it uses codes that you are programmed

and familiar with. If you attribute a high value on the initial judgments that

you form about a movie, then your experience (your present self) will mean

little because it was tainted with the strong belief of what it should have

been (your Remembering Self). Now, that we have discussed the factors which

form ones Attitude towards cinema, it is time to move on to the Subjective

Norms which stem out of Culturally based codes as well as the influence of the

other.

Subjective Norms

Trends

Trends (the general direction in which

something tends to move) can stem from and reflect our social (Racial Identity, Feminism, etc), political, aesthetic, and

philosophical beliefs (Social Narratives) as well as come out of the supply and

demand formula. In the past, social or meta narratives have created aesthetic

movements such as Surrealism, Existentialism, and Socialist Realism all of

which appear in the world of cinema (Surrealism - Luis Bunuel, Existentialism -

Jean-Luc Godard, and Pier Paolo Pasolini, and Socialist Realism - Sergei

Eisenstein, and Vsevolod Pudovkin). These trends develop out of the need to shift

or progress human thought; which then leads to trends that are formed out of

the supply and demand model. When a new or exciting work of art is created, it

immediately creates a demand for more works that are similar in nature, thus

leading to an increased production of similar works, forming a trend. This is

evident in the increased production of films using the IMAX form factor, motion

capture, and the fairly recent revival of stereoscopic images (3D), which is

present in cinema today. This is also leads the overall hype about it. The trend forms

the new movement while the hype creates the excitement for it. Hype can be

created by arousing the interest of the public with teasers and trailers, as

well as sustain it’s inertia or increase it’s momentum through Box Office

Statistics.

(Movie Poster Trends)

(Movie Poster Trends)

Hype

The two stages of hype include,

the initial anticipation of the object and the latter praise or disapproval,

which either sustains the interest or diminishes it. For example, James

Cameron’s Avatar (2009) developed an aura of novelty and innovation.

Through the hype about the specialized technology used, as well as all the

specialists (Linguists, Anatomical Experts, designers, etc) hired to develop

the film; created the expectation of something new, and revolutionary. However,

what people encountered was an old story wrapped in an aesthetically

pleasing package. Some left the theatre disappointed, because they

attributed the plot with a higher weight than the visuals, and others left

pleased because it matched their expectation. Furthermore, hype may come from a

variety of sources, each weighted differently according to their importance or

assumed credibility. For example, one might generally disagree with the

majority of the reviews from Rotten Tomatoes. So, when they see a high or low

review of a film they are interested in, it plays a smaller part in one’s

attitude towards the film because they have assigned a lower value to its

credibility.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we can see that

there are a number or operations present, regarding spectatorship, that have

some sort of effect on the way you receive and evaluate what you will see. The

expectations we have for film come from our predisposed Attitudes and Subjective

Norms which we have developed long before we have even seen the films in

question. When a film reaffirms these preconceived notions we are able to

decode the meaning behind it, which ultimately gives us pleasure and enjoyment.

Our expectations are not fixed, they can be transformed and expanded; as long

as we engage with new modes of filmic discourse. However, we will always have

some sort of idea of what cinema is, which will inevitably lead to our

expectation of what it should be.

*1 The term film or movie is used deliberately not to be confused with Christian Metz’s theory of the Cinema’s Signifier visible in “Loving the Cinema; Identification, Mirror; Disavowal, Fetishism” from The Imaginary Signifier.

*2 The concept of Dominant, Negotiated, and Oppositional Stances refer to Stewart Hall's Theory Of Encoding and Decoding meaning from "Encoding, Decoding"

Bibliography

Works Cited

Ajzen, Icek, and Martin Fishbein. Understanding Attitudes and

Predicting Social Behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1980.

Print.

Fishbein,

Martin, and Icek Ajzen. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An

Introduction to Theory and Research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Pub.,

1975. Print.

Hall,

Stuart. "Encoding/Decoding" Critical

Visions in Film Theory: Classic and Contemporary Readings. By Timothy

Corrigan, Patricia White, and Meta Mazaj. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's, 2011.

77-88. Print.

Metz,

Christian. "Loving the Cinema; Identification, Mirror; Disavowal,

Fetishism." Critical Visions in Film

Theory: Classic and Contemporary Readings. By Timothy Corrigan, Patricia

White, and Meta Mazaj. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's, 2011. 17-33. Print.

Raymond Bellour, "The

Obvious and the Code" aka, "L'Evidence et

le code," in Cinema:

theorie, lectures, ed. Dominiquc Noguez (Paris: Ed. Klincksieck,

1973

No comments:

Post a Comment